Sunday, March 27, 2016

30 Years Later Art Now Available

All of the artwork for the 30 Years Later show, now on exhibit at Gallery 1988(West) is online for viewing/purchase, including 3 cut paper pieces by me. See them here.

Friday, March 25, 2016

Opening Tonight

If you are in Los Angeles be sure to visit Gallery 1988 (West) for the 30 Years Later show celebrating movies from 1986. I have three pieces in the show.

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Lucas 30 Years Later

Here's my final piece for the 30 Years Later show at Gallery 1988 (West). This was inspired by the movie Lucas (1986) and done in 3-D cut paper. The show opens tomorrow night and runs through April 9, 2016.

Wednesday, March 23, 2016

Aliens 30 Years Later

Here are two of my pieces for the 30 Years Later show at Gallery 1988, which pay tribute to movies from 1986. I already tackled Alien for a different show, and this gave me an excuse to pay tribute to the first sequel.

The show opens this Friday, March 25, and runs through April 9, 2016.

Tuesday, March 22, 2016

Opening Friday

If you are in Los Angeles, stop by Gallery 1988 (West) to check this out. I have three pieces in the show which I will start previewing here tomorrow.

Wednesday, March 09, 2016

Screenplays into Comics

After much delay, here is my response to Adam Spade's question from a couple months ago. It's something I could have gone into much greater depth on, but I think my response is enough to provide some things to consider and a place to work from.

Adam's question:

I'm a screenwriter and I intend to create a comic series. I would like to write in screenplay format and then adapt to comic, basing the story arc on a 90 page screenplay. The comic script is still unnatural to me. I would then build on/modify the script into comic script format.

I was wondering if you have any thoughts on this. I'm open to any suggestions at this point.

1) Just writing a 90 page script and then cutting out comics based on sequence, which would probably spew 8-10 comics based on an 8 sequence structure, or

2) simply writing short screenplays, if there is an estimate number of pages in this format that would roughly equal 22 comic pages, like 1 page = 1 minute in motion picture, that I could base length on.

But I was thinking, because of the flexibility of working with panels and pages, is it really based on writing the sequence comfortably, and then making it fit in 22 comic pages?

My response:

It's not the worst way to approach writing a comic book. A number of comics began as unsold screenplays that were translated to the new medium. There are a few things to keep in mind.

1. Time in a screenplay is much different than time in a comic book. In a screenplay you can write screen directions like: THE VILLAIN TURNS AND FIRES HIS GUN AT THE POLICE, THEN RUNS ACROSS THE ROOM EVADING RETURNING GUNFIRE. HE LEAPS THROUGH THE CLOSED WINDOW, SHATTERING THE GLASS AS HE DOES SO. BULLETS IMPACT ALL AROUND HIM, BUT NONE HIT HIM.

That's quick. In a screenplay, it takes up about as much of the page as the type above. In a film that sequence can be mere seconds long, or a bit longer depending on the director and editor, and the effect they are going for. In a comic book that's a minimum of three panels, and not small panels either. It could easily be the entire page of a 22 page comic book. Each action requires its own panel. One panel: Villain turning and firing his gun at the police (which could be two panels if you want to cut between him and the police rather than having both in the same panel). Second panel: Villain running across the room. Third panel: Villain leaping through the window as he's fired upon. Again, like the director/editor inserting more reaction shots to build the scene, the artist could easily add panels to this sequence to draw it out.

When I wrote the X-Files comic book series, the people producing the show initially didn't like the narrative captions that I was using because they felt that the narration used in the captions was not representative of the tv series which only occasionally used narration (in the form of Mulder or Scully in voice over) to open or close an episode with their reflections on what happened.

I explained that this was a narrative necessity. On the show a character could pick a locked door and open it in seconds going through the process of noting the door being locked, reaching into their pocket for lock picking tools, producing the tools, picking the lock and opening the door. In a comic book you could either take up an entire page showing all of those steps, or use one panel with a narrative caption explaining that the lock was being picked, or a line of dialogue saying "I'm going to pick the lock."

2. In a screenplay, description of settings, props, actions, expressions, etc. is kept to a minimum. If it's a story set on a spaceship, you just have to say it's a spaceship, and maybe if it's clean, run down, or cramped. You don't know what the movie's budget will be. You have no notion of what the director's idea of what the spaceship should look like, or the production designer's. You can't control actual locations either, whether it's a park, a house, or a grocery store. Likewise, the directors, costume designers, and actors will determine the look and performances of the characters. The screenwriter has no say which makes the process of writing a screenplay less time consuming than writing a comic book script.

In a comic book, assuming a separate individual, other than yourself is going to be handling the art chores, you need to describe everything. If you have a spaceship, you need to describe everything about what it looks like on the outside and the inside, plus how all of the rooms connect and what's in them. Ditto props, especially the important ones, costumes, the physical appearance of the characters, what their body language is like and how that body language changes depending on what other character is with them, or what the situation is. You have to include facial expressions, too. If you set something in an outdoor location you need to decide on the time of year, day, weather, if there are trees and what kind, how many, and on what side of the panel they will appear on.

With this in mind, you also need to accept that your artist may see things somewhat differently than you do and let them draw it their way, unless there is some logical reason not to (such as an important plot point requiring your character to have green eyes -- which, if it is important, needs to be spelled out as such at the beginning, even if that plot point won't rear its head for another five issues). Even though you need to let your artist adjust things and trust them to bring their skills to the story in a way that enhances your script, it's still important, at least I think so, to saturate them with information so that they understand where you are coming from, and what you are looking for, even if they choose to ignore some of it. With more information, they'll be better equipped to adapt and streamline the storytelling as well as sell the world your story is set in.

Because of all of this a comic book script is typically denser than a movie script. Most movie scripts are 90-100 pages long with the idea that each page accounts for roughly a minute of screen time. I've written comic book scripts for 22 page stories which ran about 40 pages long due to the amount of new visual information that needed to be conveyed to the artist. On a new series, the early scripts tend to be longest, since more needs to be described as it is established, but over time, and as the relationship between writer and artist builds, the scripts will shrink to something closer to a one page of script = one page of finished comic book ratio.

You need to be able to break your scenes down page by page and panel by panel, preferably beginning a scene in the upper left panel of a page and ending on the lower right panel of that page, or another page, depending on the length of the scene. You'll also need to make sure that your story, or installment of the story, comes to a satisfying conclusion at the end of the allotted amount of pages (usually 20-22). As you now realize, on the amount of space needed for a comic book scene is variable, so that there's no real analogue to the 1 page = 1 minute of screenplay ratio for screenplays. Now, to address your other idea of breaking your script down into segments that approximate 22 pages of comic book storytelling, you may have figured out the central obstacle to doing this. While each comic book needs to end on a satisfying story point, often a cliffhanger which will make your reader want to return for the next installment, a screenplay doesn't divide that neatly, especially using the three act narrative structure. This means restructuring your story into smaller arcs that end with dramatic high points in order to adapt it to the needs of a comic book format.

Here are some examples. Go Into the Story has a wide range of screenplays that you can read for free. Since we were talking about spaceships, take a look at the screenplay for Gravity. Notice how little description there is of the environment, the characters, their actions, props, etc. It's really bare bones since those things will be determined by budget, casting, art directors, directors, special effects people, other crew members, etc. Almost everything in the screenplay is dialogue with no demarkations to determine how long it will take to say it all, or what the characters will be doing specifically with each block of dialogue.

With a comic book, you can't simply transpose what's in a screenplay by passing off what's there tho an artist. All of that dialogue will have to be broken down panel by panel (and almost certainly truncated) with instructions in each panel as to what is going on visually at the same time. Keeping that in mind, in a movie, speech is invisible, and no matter how much speaking is being done, it doesn't obstruct the view of the action. In comics, dialogue is a visual component and it will have to be taken into consideration as one in order to leave enough room for the artist to draw what needs to be seen and also accommodate the text.

Space craft need to be described, which characters are in the panel - and what each of them is doing, whether one is in the foreground, or middle ground, facing us, or something or someone else. What the lighting is like, what the characters look like, what emotions their expressions are conveying, and so on -- everything that is absent in the screenplay needs to be introduced for the comic book script.

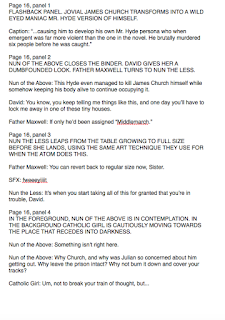

Below are two unconnected pages of the script for Xombi #1. There's no set format for a comic book script, but this is how I've always done it, and no one has ever complained. One page includes the description of a new location, done with the idea that not all of that would be seen, or seen in a single panel, but allowing for the artist to understand the environment in such a way they could adapt it to suit the storytelling. The second page conveys character interactions.

You'll notice a lot of intangible elements being described such as one character contemplating. There are also sound effects included, which is another element often left out of screenplays.

I think if you have a finished screenplay, or if that's the format you're comfortable with, then by all means, use it as starting point. You can see by the examples above that the format itself is not too, too different. Break your story down scene by scene. Figure out what is important about each scene. Mark that as what absolutely needs to be hit upon in the comic and truncate/add dialogue and action as necessary to make it work for a comic book story.

Definitely look at some comics and look at how much dialogue is used per panel. You'll find it's generally a line or two. The dialogue is also often written in a way that suggests natural speech but isn't the way people really talk. That's because of the space limitations. You may end up having to pare down your own dialogue to make it work for comics. You'll also notice that rhythms can be created but may require more panels than you intended.

Also remember, in general, one action per panel. Action scenes generally use fewer larger panels per page, so they read faster. Dialogue scenes use more panels, depending on the amount of text) because other than the expressions of the characters we don't need to devote a lot of space to action and setting. It really is often like talking heads.

Sunday, March 06, 2016

Monster! #26 Now Available

The latest issue of the zine devoted to all things monster is now available on Amazon featuring a cut paper cover by me illustrating Ladron de Cadavers. This is an excellent publication, covering a lot of movies, and other areas of monster entertainment, that you won't find anywhere else. This particular issue, I believe, contains 123 pages of material, all for $6.95. I also highly recommend the back issues, all of which are available via Amazon.com.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)